The OceanXplorer, one of the most technologically advanced vessels ever created, takes scientists and filmmakers to the most remote waters in the world. The ship’s onboard helicopter allows them to venture even further.

After giving birth, leopard seals raise their young in hole-like dens the females cut into the Antarctic ice. To protect the young seals as they learn to forage for themselves, adults bore diving holes through thick ice sheets far from the open ocean that are hard to find, especially for ship-bound scientists and filmmakers trying to learn about their behavior.

Unless, that is, the scientists have a helicopter. Even the OceanXplorer, one of the most technologically advanced research vessels afloat, can only get so close to the seals’ diving holes. And then there is the matter of transporting heavily outfitted scientists and wildlife photographers and their gear inland to record the animals. Leave that to the ship’s onboard Airbus H125, specially outfitted for operations from the deck of the OceanXplorer to the ends of the earth.

“There are extremely few helicopter operations in Antarctica to begin with, let alone from a vessel,” said Mark Dalio, founder and creative director of OceanX, the ocean exploration initiative that owns and operates the OceanXplorer. “We were able to deploy teams onto some of these remote ice sheets where we were trying to film these seals going into these diving holes that they created, and otherwise we would never have been able to deploy a team to film them.”

Having the helicopter on call enabled to the team to “quite quickly find the location that we needed from the air and then deploy a team to track and film” the seals. Travelling that distance from the ship on foot would have been treacherous, if not impossible.

Aside from icebound seals, OceanXplorer’s helicopter has been instrumental in filming and studying whale behavior on the open ocean, finding and recording migrating manta rays, and filming terrestrial natural wonders like volcanoes in Papua New Guinea and the Galapagos.

Sometimes, when the helicopter is being used to scout for specific animals or environments, it hits the jackpot and captures more than planned. While filming the nesting habits of megapode birds in New Guinea — in lieu of incubating their eggs, the large birds bury them in mounds of vegetation around the rims of volcanoes, which warm the embryos — the helicopter was in the air for an unplanned eruption.

-

Flights are usually scrubbed if the sea is pitching or rolling the boat more than four degrees.

Flights are usually scrubbed if the sea is pitching or rolling the boat more than four degrees.

“It started to erupt with big boulders and chunks of rock flying out of the crater,” Dalio said. “Sometimes it comes down to minutes, sometimes 20 minutes, 10 minutes, that you get the shot that you need or you don’t. The helicopter is that essential asset that allows us to gain those crucial minutes or an hour or so that might make or break a sequence that we’re doing.”

Adventure Aircraft

OceanX’s deceptively simple mission statement “to explore the ocean and bring it back to the world” is accomplished by a crew of more than 50 manning a fleet of highly sophisticated aircraft, surface vessels and submersibles in some of the harshest, most remote seas.

The effort to offer months-long voyages to both scientists and filmmakers began in 2012, when Mark Dalio founded Alucia Productions (now OceanX Media) with the organization’s first ship, the 184-foot (56-meter) motor vessel Alucia, which launched with an Airbus EC135 aboard.

“That one was originally purchased with us not really knowing the type of operations we would be doing,” Dalio said. “That was very early on in our existence…. The EC135 is a nice helicopter maybe for transporting people and is fairly comfortable, but it’s not the pickup-truck helicopter that we needed.

“We needed to be able to haul gear,” Dalio continued. “We need to maneuver in tight situations for filming and operations and then deploy assets from the helicopter, whether it is people or equipment or gear in various locations that made it a little more difficult using the EC135.”

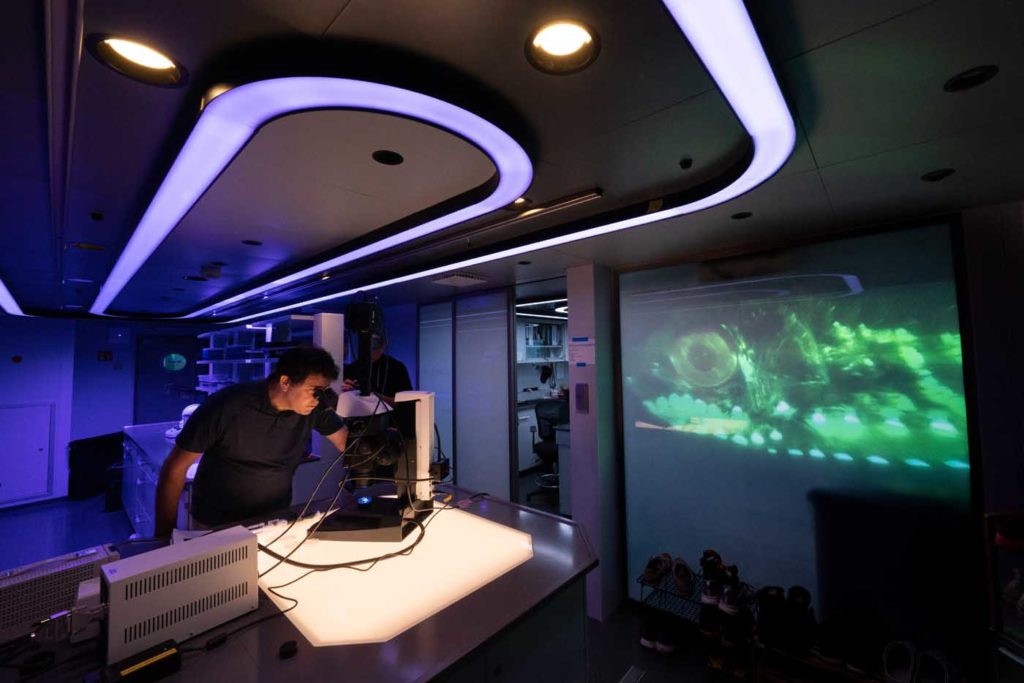

In 2019, the company took on the name OceanX and launched the 285-foot (87-meter) OceanXplorer, a purpose-built marine science and media vessel with a helipad and hangar affixed to its bow. The ship features state-of-the-art onboard dry and wet marine research labs, cutting-edge media equipment in a production and media center, manned and autonomous deep-sea submersibles, and the capability to carry and launch various drones.

“The 135 was a great machine; it’s a great-flying aircraft, but we were bumping up against the aircraft’s performance limitations just about every mission just to keep that safety margin of fuel,” Tyler Sturdevant, an OceanX pilot and check airman, told Vertical. “So, the group got together to see what aircraft would meet all the mission profiles and give us that margin of safety that we’re looking for. We all kind of came to the conclusion that it was the B3 Echo [H125]. . . . It has exceeded all our expectations.”

Outfitted with pop-out emergency floats and auto-deploy life rafts, a Cineflex camera on the nose and all the high-tech cinematography equipment required to capture high-definition footage, the seven-seater AStar has become indispensable to OceanX’s various missions, said pilot Lee Rhodes.

“Most of the things that we have spotted that have been noteworthy, that have been extraordinary . . . have been further from the boat than any of the support craft could have gotten to or any drone, certainly, could have gotten to,” Rhodes said. “When we do come across something that we want to get footage of, the fact that we can stay there for so long and get as much footage as we want [is beneficial] versus the time limit on a drone.

“It has, essentially, every option I think you can put on a helicopter as far as avionics,” he continued. “It has the float system built in with life rafts in the back that deploy with the floats. It’s got the camera mounts, it’s got A/C. . . . It’s set up to do anything you need it to do.

“You can debate [about] going from a twin, over open ocean most of the time, to a single — that’s a lifelong debate in the helicopter community, of course — but I think it was absolutely the right choice,” Rhodes said. “The capabilities of this machine, the power it has, the size, I think is perfect for what we’re using it for.”

The OceanXplorer is designed with a helideck on the bow, which Rhodes said is uniquely challenging because at sea it is the part of the boat that heaves most with the waves. But the new ship also has a hangar adjacent to the helipad into which the helicopter can stow using a Tiger Tug. That cuts down on the time it spends in the salt air and spray.

“We have procedures where we don’t launch from land until I talk with the ship on the phone and get the location. We were normally able to get radio comms with them within about 60 or 70 miles (95 to 115 kilometers) of the ship. Communication was key.”

“We have a blade-fold kit, so if we’re going to do a really long crossing or we’re expecting really bad weather, we’ll pull it in so it’s out of the weather and protected,” Rhodes said. “It makes it great for maintenance, too.”

Basing a helicopter aboard an oceangoing research vessel requires careful attention to maintenance and both Sturdevant and Rhodes extolled mechanic Gordy Mabey as a “rockstar” who is almost single-handedly responsible for the success of aviation missions. It is Mabey’s job to rinse the exterior of the helicopter twice a day, and constantly clean and apply anti-corrosive to critical flight components. With OceanXplorer’s onboard hangar, Mabey has the facilities and tools required for blade replacements and has changed out a full authority digital engine control (FADEC).

“Maintenance is critical in that environment and having a good mechanic who takes pride in their work was huge and I think what made us so successful,” Sturdevant said. “I think there were only two flights I had to turn down because of a maintenance issue.”

Precision Mission

While OceanX owns its aircraft, from the start, aviation services — including pilots and maintenance — have been provided by McMinnville, Oregon-based Precision Aviation.

Precision supplies a pilot-mechanic team. The mechanics are often also flight qualified, so they can act as a safety pilot.

Both the ship’s crew and aviation team prepare to deploy for up to three months at a time to remote locations. While voyaging to the Galapagos, everyone involved knew that the nearest official rescue facility was on mainland Ecuador, 600 miles (965 kilometers) and many, many hours away, Sturdevant said.

“There’s a little bit of a risk element there, which means you have to make sure that you really do your homework and you do your prep work and understand what those risks are and how to mitigate them and then communicate that with the team,” Sturdevant said. “We have procedures where we don’t launch from land until I talk with the ship on the phone and get the location. We were normally able to get radio comms with them within about 60 or 70 miles (95 to 115 kilometers) of the ship. Communication was key.”

Everyone involved with the ship and helicopter is conservative with making the call whether to fly, given the sea state and weather forecast, Sturdevant said. Winds above 35 knots would usually force the helicopter to stay on deck. Flights were typically scrubbed if the sea was pitching or rolling the boat more than four degrees.

“We have an important mission, but we were never dealing with life-and-death,” Sturdevant said. “We always kept it in our mind that we’re out here to support science and to get media but no one’s dying if we don’t launch today.”

Tagging whales or sharks is a job for scientists aboard rigid-hull inflatable boats or diving beneath the surface, but those tags are small and often difficult to find in heavy seas once they break loose from an animal. In such cases, the helicopter can find the tag and relay its location to boat crews so they can retrieve it and download the data it holds.

Sometimes both science and filmmaking take a back seat to more pressing missions. While on separate voyages to Costa Rica in Central America and Vanuatu in the South Pacific, OceanX responded to humanitarian needs in the wake of devastating hurricanes, deploying the helicopter to perform aerial surveys and to deliver fresh water to victims, Dalio said.

Typically when flying from the ship, OceanX pilots return and land with at least 20 minutes’ worth of fuel in reserve, as per FAA guidelines, Sturdevant said.

“I like to have 45 minutes to an hour,” he said. “It would change, depending on the mission. If my emergency escape was an hour away, we were definitely going to have an hour’s worth of fuel on board when we got back.”

About three months prior to an OceanX voyage, Precision teams with the science and media staff to establish what mission profiles and film projects are feasible in a given location. Precision helps navigate local aviation regulations and restrictions.

“It’s different for every country we got to,” Sturdevant said. “They all have their own regulations and we have to be sure we’re following those. About three months to a month before we leave, that’s when we combine notes and make sure what is wanted and what is expected is actually feasible.”

A former airborne firefighting pilot, Rhodes dabbled in several aviation sectors — aerial news gathering, helicopter EMS, flying for the U.S. Forest Service in Alaska, heliskiing — before landing at Precision and working with OceanX.

“[The helicopter] has been instrumental, not just in what we can film, but guiding crews in small boats, the Zodiacs and support boats over to where action is happening,” Rhodes said. “We can just cover so much more ground and see what’s below the surface. From a boat, you can see a [whale] blow now and then; you can see a whale surface, but you don’t know what you’re actually looking at.”