The early development of the helicopter industry on the West Coast owes much to one of the lesser-known industry pioneers, Herman A. Poulin. His company, Central Aircraft, based in Yakima Valley, Washington, introduced helicopters to agricultural operations, and was also one of the first to operate the machines in the mountains.

Poulin’s interest in aviation can be traced back to his early childhood. As a young man, he obtained his pilot’s license and became an accomplished aviator and instructor, eventually specializing in crop-dusting with fixed-wing aircraft.

In 1939, Al Baxter, a young pilot and entrepreneur, started Central Airways — a crop-dusting business — in Yakima Valley. At that time, Yakima County was the fourth richest agricultural area in the United States. The company quickly grew to operate 50 Stearman Model 75 and 12 Waco 10 aircraft, later purchasing a surplus Boeing B-17

bomber. Central Airways was renamed Central Aircraft Inc., with Poulin appointed president and Baxter as secretary-treasurer. It flourished into the mid-1940s with successful spraying and dusting programs.

Over in Niagara Falls, New York, Bell Aircraft Corp. had entered into helicopter development at the end of the Second World War in 1945. With the success of his experimental Model 30, president Larry Bell was considering a new post-war industry — the commercial use of helicopters. He had 11 pre-production Model 47 helicopters manufactured for training and experimental work between 1945 and 1946, with plans to build 500 production versions. Soon, he was considering new types of work for his helicopters — including spraying and dusting crops and orchards.

Bell contacted Central Aircraft in Yakima to suggest using the helicopter for experimental dusting and spraying trials during the summer of 1946. Poulin was enthusiastic, welcoming the opportunity to use a helicopter in this new type of aerial operation.

Poulin was trained to fly helicopters by Bell test pilots, including chief pilot Floyd Carlson, before Bell started instructing at its new helicopter pilot school in Niagara Falls.

A pre-production Bell Model 47 was shipped to Yakima Washington in June 1946, and experimental flying started across the farming area. Frank H. (Bud) Kelley Jr., assistant to the president of Bell Aircraft, supervised helicopter operations, and mechanic Joe Beebe oversaw maintenance and mechanic training. Poulin was the main pilot for the Bell 47 helicopter and Central Aircraft’s Joe Scaman was the insecticide specialist.

“Besides its ability to fly at any speed and to back into tight corners for specialized dusting jobs, the helicopter is more effective in straight dusting or spraying because the strong downwash drives the insecticide into the foliage, reaching every bud and leaf,” Kelley said.

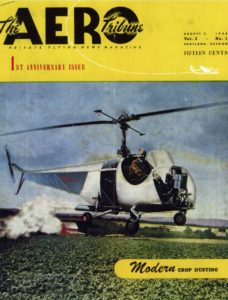

Farm owners and operators of fixed-wing aircraft were keenly interested and, overall, flight tests with the Bell 47 were successful during the summer months. The work was completed in cooperation with recognized leaders of agricultural aviation and other specialists, and the helicopter dusted hundreds of acres of orchards, trellis and flat

crops. Poulin did most of the flying, to determine the best speeds and altitudes for coverage and control. Even with light loads, the helicopter covered 20 acres in about 17 minutes, applying 50 pounds (22 kilograms) of treatment per acre.

“I’m satisfied that the helicopter will, in the near future, replace most fixed-wing airplanes for pest control,” Poulin said. “Its variable forward speeds and air effect make it possible to obtain the desired flow of materials for the particular result more effectively. Longer hours will be made possible. In addition, long ferry flights from landing strips will be eliminated. I believe these advantages will make it possible for one helicopter to do the work of at least two conventional aircraft.”

Central Aircraft ordered nine Bell 47s to start a pilot training school for crop dusting, spraying, and other agricultural uses, as well as for special projects that included snow surveys, timber cruising and fish stocking.

Meanwhile, Tommy Hall, future chief rotary-wing pilot at Central Aircraft, attended Bell’s fourth pilot training school class, graduating in 1946. His unique skills were passed to many students in the following months across the Yakima farming area.

Bell awarded Central Aircraft the first-ever helicopter dealership in the spring of 1947, covering the states of Washington and Oregon. This contract authorized the company to sell new Bell 47 helicopters, supplies and parts, and to provide repair and maintenance services.

Central Aircraft received the first Bell 47B cabin-type wheel-equipped helicopters, shipped by boxcar from Bell, in early 1947. Poulin and Hall flew demonstrations for interested farmers and dignitaries at the Yakima Airport. One interested party was the Bonneville Power Administration, who then hired Central for a three-month experimental helicopter patrol of 2,500 miles (4,023 kilometers) of powerlines in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. The future looked bright for Central Aircraft.

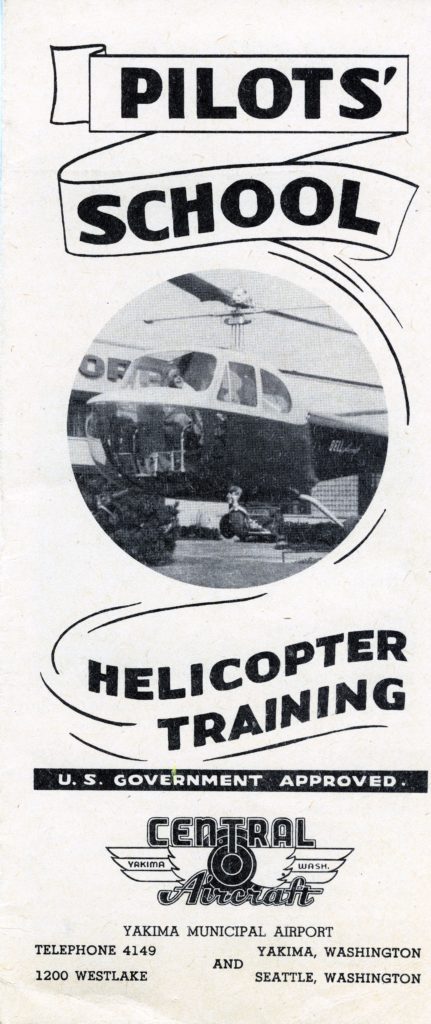

Building a training program

U.S. government-approved helicopter pilot and mechanics maintenance courses were soon underway at the Yakima Airport, under chief pilot Hall, with Beebe as instructor for maintaining the rotary-wing aircraft. Flight training, helicopter mechanics and crop-dusting courses were offered at a cost of $1,500 for 20 hours of helicopter flight instruction, plus ground school.

Angus McArthur, Vern Montgomery, Carl Brady and Kermit Jones were some of the pilots trained, and mechanics included John Brink, Stan Hellwick, Bill Brown, Danny Grecco and Wayne Cooper.

In the early spring, the U.S. Geological Survey department used a Bell 47B on floats for experimental snow surveys on the eastern slope of Cascade Mountain. The program was completed in record time using one geological engineer, compared to the previous need to have more than a dozen men on skis for over a week.

Central Aircraft received two more Bell 47B helicopters in late April, and set up headquarters in Seattle, Washington, to carry out training using its float-equipped Bell 47B. Then, in early May, Central ferried a Bell 47B on floats to Vancouver, British Columbia, to participate in the search for a missing Trans Canada Airlines Lodestar airliner that had crashed while landing in Vancouver. However, the crash site was not located and the remains of the aircraft were only discovered 47 years later on the North Shore Mountains, near Vancouver.

Central Aircraft suffered its own disastrous crash on May 7, 1947, when pilot Angus McArthur lost control while attempting an autorotation during a landing on Lake Union, near Seattle. McArthur and his passenger were both killed in the accident.

Two months later, Central Aircraft received three new agricultural open-cockpit two-place crop dusting helicopters from Bell.

Also that spring, Okanagan Air Services pilot Carl Agar and engineer/mechanic Alf Stringer arrived in Yakima from Penticton, British Columbia, for training on the Bell 47. Okanagan Air Services purchased one of Central’s Bell 47B-3 helicopters, and Agar flew back to British Columbia on Aug. 9, 1947, after he completed his flight training.

In mid-August, Brady and Montgomery ferried a Bell 47B to Vancouver Island, where it was used in an attempt to recover the body of a mountain climber trapped at 4,000 feet (1,220 meters) on the Tiedman Glacier, Mt. Waddington. However, mountain flying techniques hadn’t been developed and the terrain prevented the helicopter

from being used successfully to retrieve the body.

By the end of 1947, Central’s pest control program recorded almost 500 flight hours of dusting and spraying through two aircraft. Work was completed on high crops, orchards and hops and the helicopters registered almost 100 percent control.

Central Aircraft continued its successful pilot training course in 1948, along with the dusting and spraying program. Hall ran the pilot training program, while Brady, a Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) examiner, started a flight training school in San Mateo, California, and graduated about 15 students. He later set up a school in the Seattle area, where he trained Nancy Livingston to fly (she was the first woman on the West Coast to receive a commercial helicopter rating).

Central Aircraft was successful in a follow-up contract for the Bonneville Power Administration, patrolling 3,000 miles (4,830 kilometers) of powerlines by helicopter in the Pacific Northwest. The power company purchased its own helicopter fleet for patrol and specialized work, and it continues to use helicopters to this day.

In 1948, Poulin supplied two helicopters and crews to the U.S. Geological Survey for a mapping survey program. When he won the contract, he had two helicopters, but just one pilot available for the job. Around the same time, Brady started his own commercial helicopter company, Economy Pest Control, with two entomologists as partners – Joe Scaman and Don Larson.

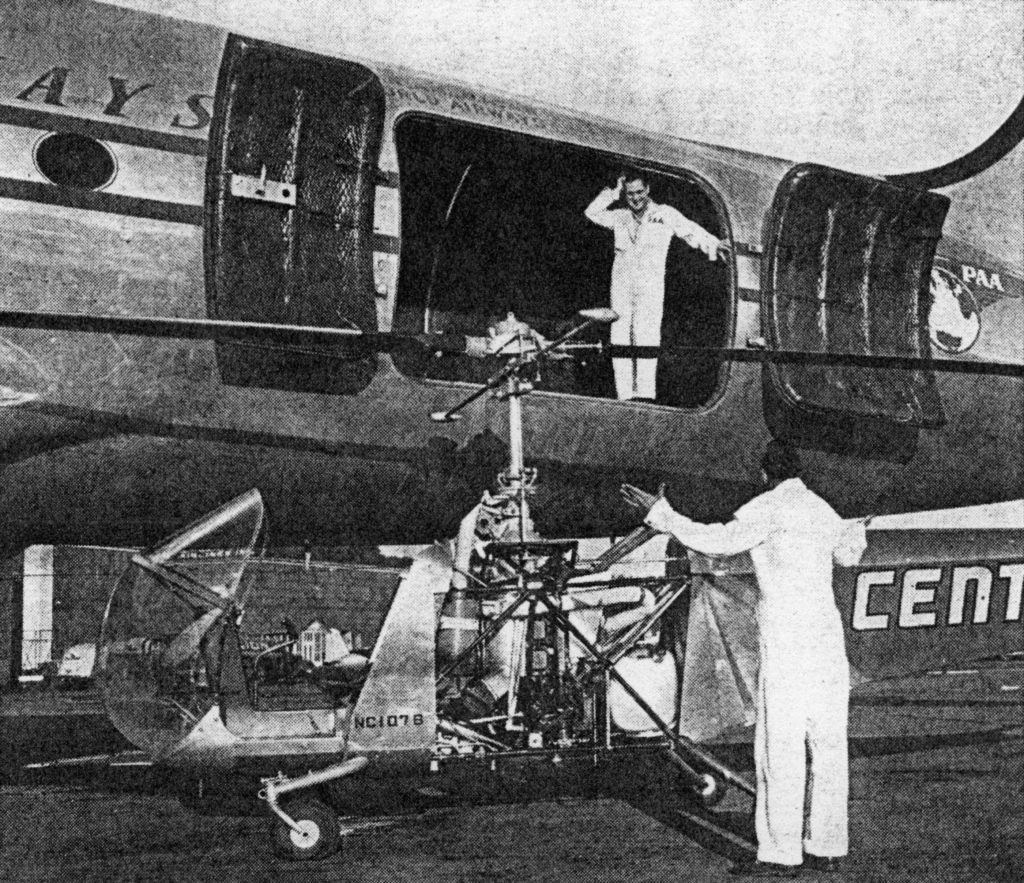

Brady agreed to fly one of the helicopters in Alaska and leased it from Central Aircraft, receiving half the revenue from the job. The aircraft had been modified with an open cockpit bubble enclosure, while the other Bell 47B cabin remained unchanged. Both helicopters were broken down and loaded into a Pan American DC-4 at the Boeing Field in Seattle for transport to Juneau, Alaska.

The job location was near Pelican and Fairbanks in northeast Alaska. The program involved flying surveyors and instruments to the tops of mountains, where they made observations related to basic triangulations for mapping purposes. It was ideal work for the helicopter.

Brady reported landing on seven mountaintops numerous times in one day, at altitudes averaging 4,000 to 5,000 feet (1,220 to 1,525 meters). Over 28 days, Brady recorded 260 mountain landings and flew 142 hours, with two forced landings due to fan belts breaking, and one because of carburetor icing. Thanks to the helicopter, work was completed in one day that normally would have taken a month if survey crews had to walk and climb on foot.

During this time, Brady came up with the idea of attaching two-by-fours between the wheels on both sides of the helicopter, to prevent sinking in soft ground conditions when landing on mountainous terrain.

Meanwhile, Hall removed the cabin enclosure on the Bell 47B flights during the summer. The view was excellent, but there was an obvious problem when it rained. Project engineers were ecstatic about using this new type of aviation for personnel transport, until the helicopter was damaged when landing in a muskeg area near the end of the

contract. It was abandoned over the winter and later rebuilt to fly again.

Overall, the first geological survey using helicopters in Alaska was an outstanding success and led to additional contracts in 1949 for several commercial companies. Brady concentrated on expanding his own company, Economy Pest Control, and purchased Bell Model 47Ds for use in Alaska.

A challenging time

Another important job for Central during 1948 was one of the first firefighting contracts with the U.S. Forest Service in Northern California. Armstrong-Flint Helicopters was awarded the original contract, but lost their Bell Model 47B in an accident — and Poulin agreed to supply a Bell 47B-3 to complete the job.

Pioneering helicopter pilot Hal Symes and mechanic Danny Grecco flew the contract starting in August. Symes had been recently hired by Poulin to fly dusting and spraying operations, after he spent over a year in Argentina dusting locusts with Bell Aircraft for the Argentine government.

Symes flew more than 125 hours in his first month, moving firefighters to numerous fire sites, landing on ridge tops to drop off men. However, the high altitudes were challenging for the under-powered helicopter.

He spent his time picking up firefighters after they fought the wildfires, carrying out surveys to locate potential sites for landing pads and other specialized jobs until the contract was completed successfully in mid-October.

By this time, Poulin and Central Aircraft were experiencing financial problems. There wasn’t enough money coming in and new helicopters were very expensive. As a result, numerous Central personnel were let go.

The following year was also challenging for Central, with crop and orchard spraying increasing dramatically and becoming a mainstay for the company, as other contracts were becoming more difficult to secure due to competition from other commercial companies.

By 1950, Central was back in Alaska with a Bell 47B mapping surveys for the U.S. Department of the Interior. Seeding programs at forest fire burn sites were also happening, along with dusting and fogging operations in Washington, Oregon and California. Profits were scarce and in December 1950, Beebe, then director of maintenance, left Central after four years, returning east to work for Bell Aircraft Inc.

Poulin concentrated on dusting in wheat country in the late spring of 1951, with Jones and Hall in charge of agricultural dusting and spraying operations in the Walla Walla and Colfax, Washington, areas, and orchard and roll crop jobs in the Yakima Valley.

In mid-April, Poulin pulled his agricultural helicopter away from dusting work and arranged for it to be sent to Alaska to work on a U.S. geological survey. Jones was not impressed, since he had several thousand acres left to spray. When he left Central, he leased a ship from Rick Helicopters in California and resumed spraying wheat a few days later. Hall also resigned, and the two ended up flying for Economy Pest Control in Alaska.

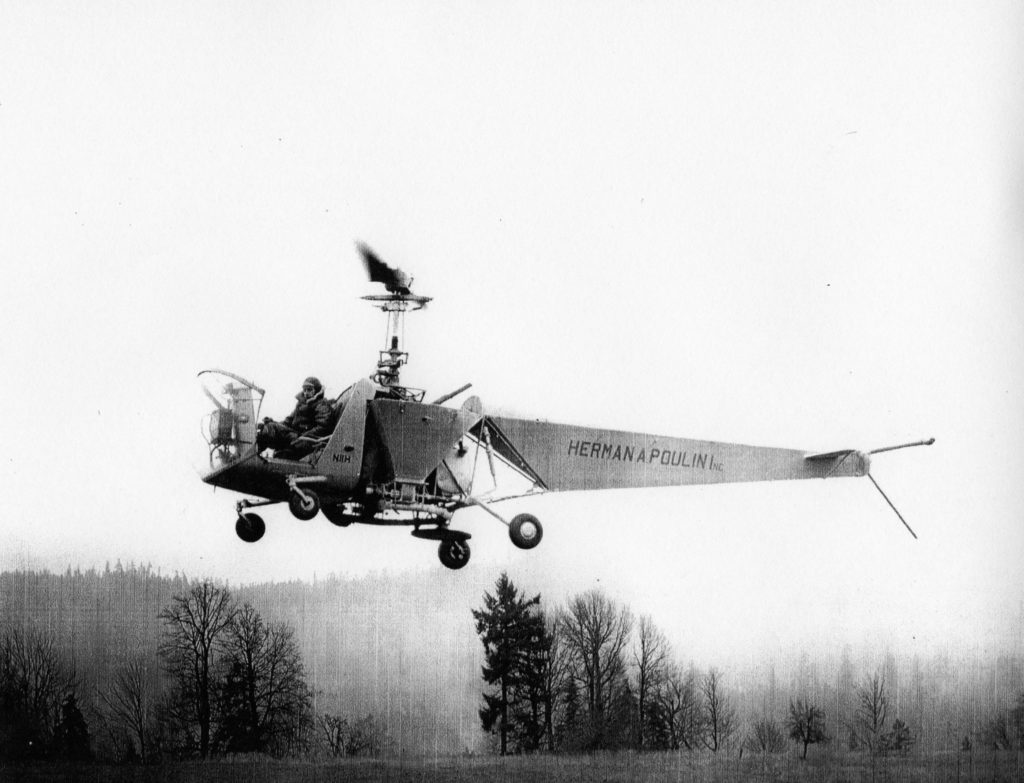

Central Aircraft’s position was dire enough to force it to declare bankruptcy. It reorganized under the name Herman A. Poulin Inc. and continued to fly in the Yakima Valley area. However, Poulin ceased operations after a few years in Yakima and moved to Oregon.

“Herm kind of faded away, but resurfaced in the early 1960s, operating a company called Reforestation Services,” Dan Jones, son of Kermit Jones, said in a recent email. “Poulin operated Hiller 12E helicopters and was heavily involved with forestry and railroad right-of-way spraying.”

Poulin died in Belfair, Washington, in 1974. He had influenced the growth of the helicopter industry from the early days of commercial rotary-wing flight, through the 1960s. His management style, skills and reputation will not be forgotten by the many people who worked for and with him.